Hong Kong’s global trade hub status and cosmopolitan society have given it a well-earned reputation as a foodies’ paradise with restaurants and shops supplying cuisine from every part of the globe.

Complex, ever-changing supply chains and substantial financial incentives to cut corners on sourcing present a challenge, however. How is a buyer to be sure the product is really Ethiopian coffee or wild-caught Norwegian salmon?

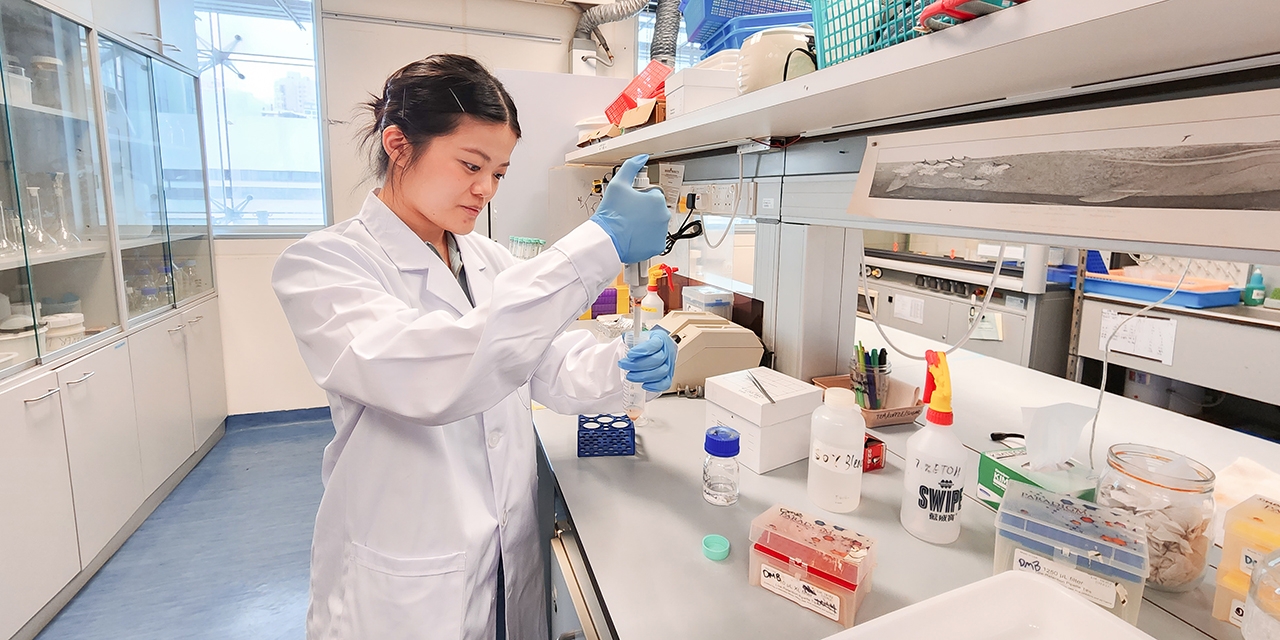

As a foodie paradise with a brace of world-class universities and thriving research community, it is no surprise that Hong Kong has produced a group of isotope fingerprint sleuths.

Key placement

The University of Hong Kong (HKU) placed a former restaurateur and coral-reef researcher at adjacent desks during their PhD programme. The students, Dr Colin Luk (now Co-founder and Project Development Lead, isoFoodtrace) and Dr Inga Conti-Jerpe (now Co-founder and Scientific Development Lead, isoFoodtrace), realised they could pool their skills and develop a system to certify the source of food items.

Our food, like ourselves, is full of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, nucleic acids and more which are in turn made up of atoms of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, among others. And the nuclei of these atoms do not all have the same number of neutrons – a small proportion of the hydrogen atoms in water, for example, are in fact deuterium, hydrogen with one proton and one neutron (most hydrogen atoms have just one proton). Proteins can also carry nitrogen 15 (with eight neutrons) as well as the usual nitrogen 14 (seven neutrons).

These variants, isotopes, occur in distinct proportions – an isotope signature – depending on where the plants or animals they came from lived. And this signature allows testing organisations to certify the place food comes from and conditions it was raised in (wild or captive, organic or not).

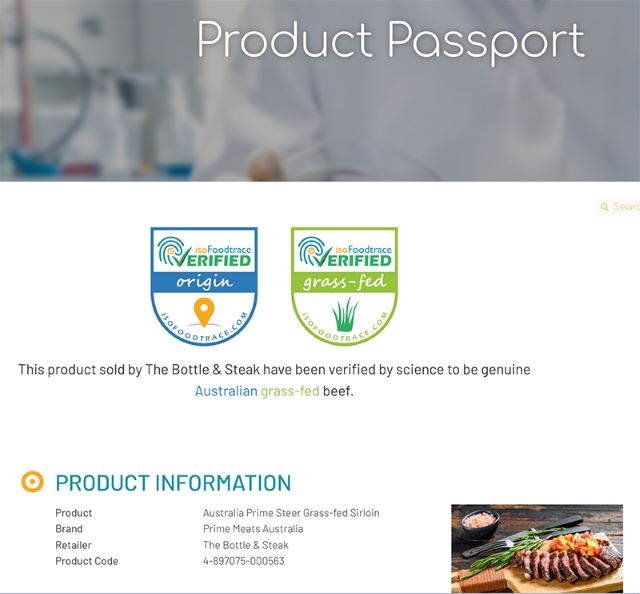

IsoFoodtrace supplies food distributors with product passports certifying origin based on isotope analysis.

Dr Luk said there was a lot of demand for such services in Hong Kong where more than 90% of food, worth US$27.6 billion, is imported.

“With our technology, we can detact the true origin of the food and its farming method. This could benefit importers to verify the goods they’ve imported,” Dr Luk said. Increased health consciousness following the COVID-19 pandemic had boosted demand.

Time-consuming

Creating isotope signatures requires a lot of legwork – examining more than 150 samples in the case of Ethiopian coffee, and 25 for wild versus farmed salmon.

Sample processing is also complex. “In most cases we would use existing academic articles as references – more specifically, the stable isotopic signature for food attributes. We also aim to discover the stable isotopic relationships between rainfall and food products: as rainfall stable isotopes can be associated with food origin by analysing the isotopic composition of water in crops or animal tissues. This helps determine geographical regions where the food was grown or raised.”

IsoFoodtrace now tracks coffee, salmon, beef and eggs. “We keep developing our database for new food product traceability, and generally it would take about two months for each food product. We hope to collaborate with the food industry, government and NGOs for related food tracing R&D,” Dr Luk said.

Enhancing Hong Kong’s role as a start-up hub, Dr Luk said isoFoodtrace had been supported by HKU through its iDendron techno-entrepreneurship core, laboratory and mentor support and funding through the Technology Start-up Support Scheme for Universities (TSSSU) Grant.

IsoFoodtrace also joined the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks incubation programme.Related links

IsoFoodtrace